Chasing Paradise: Art in Japan's Philosophical Tradition

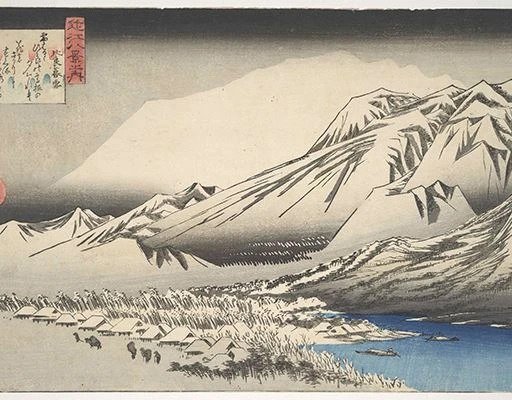

Even the briefest glance at Japanese art over the centuries establishes it as an entirely different tradition than that of the West. In some sense that is an intuitive, even obvious statement. The landscapes of Utagawa Hiroshige and Caspar David Friedrich, for instance, have in common almost exclusively their subject matter. Their methods of expressing perspective, atmosphere, ambience, and even basic form are completely different.

Even among the most well-meaning art historians, however, in the world of cultural exchange it is always necessary to fight against the tendency to stop at “different.” No matter how deeply one comes to understand a foreign culture, it is easy to view the world as if one’s own culture was the default. While such a mindset can be useful – even necessary – to orient oneself in the world, it outlives its purpose when it becomes not a “home-base” but a yardstick to evaluate all that is “other.”

Many people have already elaborated on the threats that such malformed judgments can pose for many cultural traditions, especially those that are now minorities, that face material poverty, or are being pushed to the point of extinction by industrialization. To specify that Katsushika Hokusai relies on lines to express form is one thing; to pluck this trait out of his work as if it were an odd divergence from Europe’s High Renaissance is to miss the entire point of the exercise. It is to have failed to explore alternative understandings of what art can be – and therefore in the end to misunderstand what art fundamentally is. With time, rather than muddying at the definition of art, exploring different cultures and art styles can clarify art’s true meaning and purpose. Read More...