Guatemala's Much-Criticized Top Prosecutor Seeks 2nd Term

Once the envy of Central America for anticorruption efforts that took down a sitting president, Guatemala’s attorney general’s office in recent years has been accused of blocking corruption investigations, protecting powerful interests and even persecuting those who pursue the corrupt.

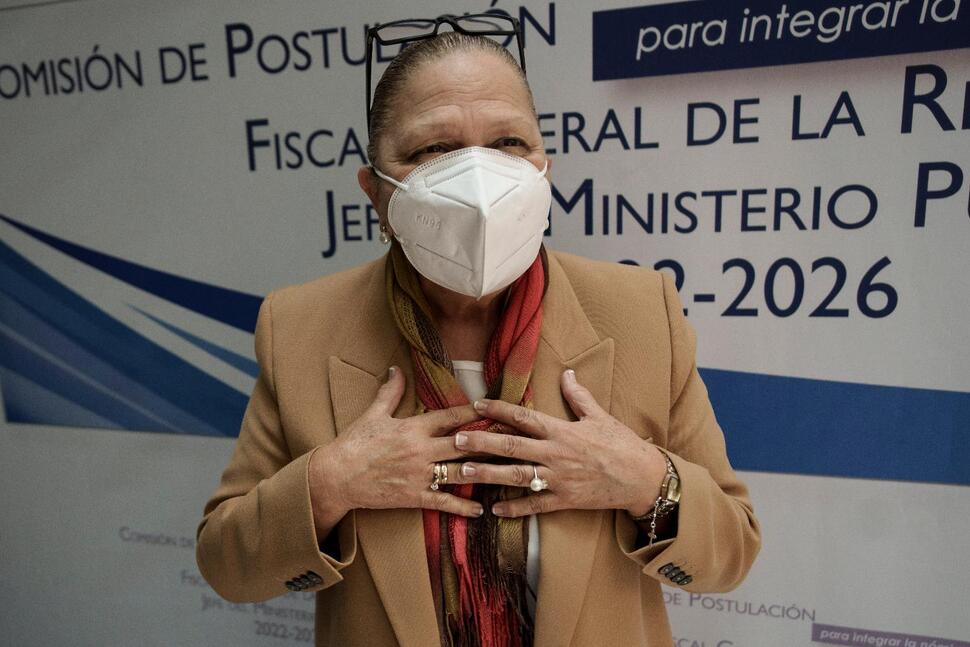

Consuelo Porras, who has led the office for the past four years, dismisses the accusations and dodges questions with legal jargon and recitations of the law. President Alejandro Giammattei defends her before Guatemalans, international organizations and the U.S. government, which suspended cooperation with her office last year and yanked her visa.

In the coming days, Giammattei must choose Guatemala's next attorney general, a closely watched decision that observers say gives him an opportunity to reanimate the country's stalled fight against corruption. But Porras, 68, is seeking a second term, one of 15 candidates for the post.

Her path to a second term is not completely clear despite her friendship with Giammattei. Among the other candidates is Guatemala’s solicitor general Luis Donado, who is also close to Giammattei.

Porras' appointment in 2018 by then-President Jimmy Morales proved to be an inflection point in her country’s battle against corruption.

She had large shoes to fill. She followed Thelma Aldana, who had pressed a number of high-profile corruption investigations including ones against Morales while he was president and some of his relatives and associates.

Aldana had already made a name for herself by jailing former President Otto Pérez Molina, his vice president and Cabinet members, after perhaps the most high-profile of dozens of probes. Aldana received asylum in the United States in 2020.

Aldana’s success against Guatemala’s systemic corruption had come in conjunction with the United Nations-backed anticorruption mission, known by its Spanish initials CICIG. Over 12 years, the mission supported the Special Prosecutors Office Against Impunity in dismantling dozens of criminal networks while at the same time building their capacity to handle complex corruption cases.

In August 2019, a bit more than a year after Porras’ appointment, Morales ended the CICIG’s mission while he was under investigation. Porras, at least publicly, did not push back in defense of the mission.

Porras, who came to the office with a background in constitutional law and as an appellate judge, initially spoke glowingly of the accomplishment’s of her office’s anticorruption work, but the people leading those efforts saw little interest on her part.

When she took office, Porras delayed meeting with Iván Velásquez, a Colombian lawyer and the CICIG’s last chief. She did anything to avoid a conversation, he said. “That was already a very bad sign."

Her lack of experience in prosecuting corruption cases and apparent disinterest made her seem an odd fit, Velásquez said.

“Not only for her personality, but rather for her inability, including to directly confront someone,” he said. “I believe that with Morales it was total submission.”

As investigations began to near Giammattei and his associates, Porras moved from disinterest to obstruction. Prosecutors and others who had worked closely with the CICIG became targets themselves.

During her term, nearly 20 prosecutors, judges and magistrates have gone into exile, fearful they will be prosecuted in retaliation for their work on corruption cases.

Asked by a reporter this month if she is protecting the president from investigation, Porras said, “we are all subjected to the knowledge of the law; I can’t protect anyone.”

Last year, she fired Juan Francisco Sandoval, who led the Special Prosecutors Office Against Impunity and who had been applauded for his work.

Sandoval fled Guatemala under cover of darkness to neighboring El Salvador just hours after his removal. Porras had vaguely accused him of “abuses” without giving details.

Sandoval said he was fired because of his investigations into top officials in Giammattei’s administration. Read More...