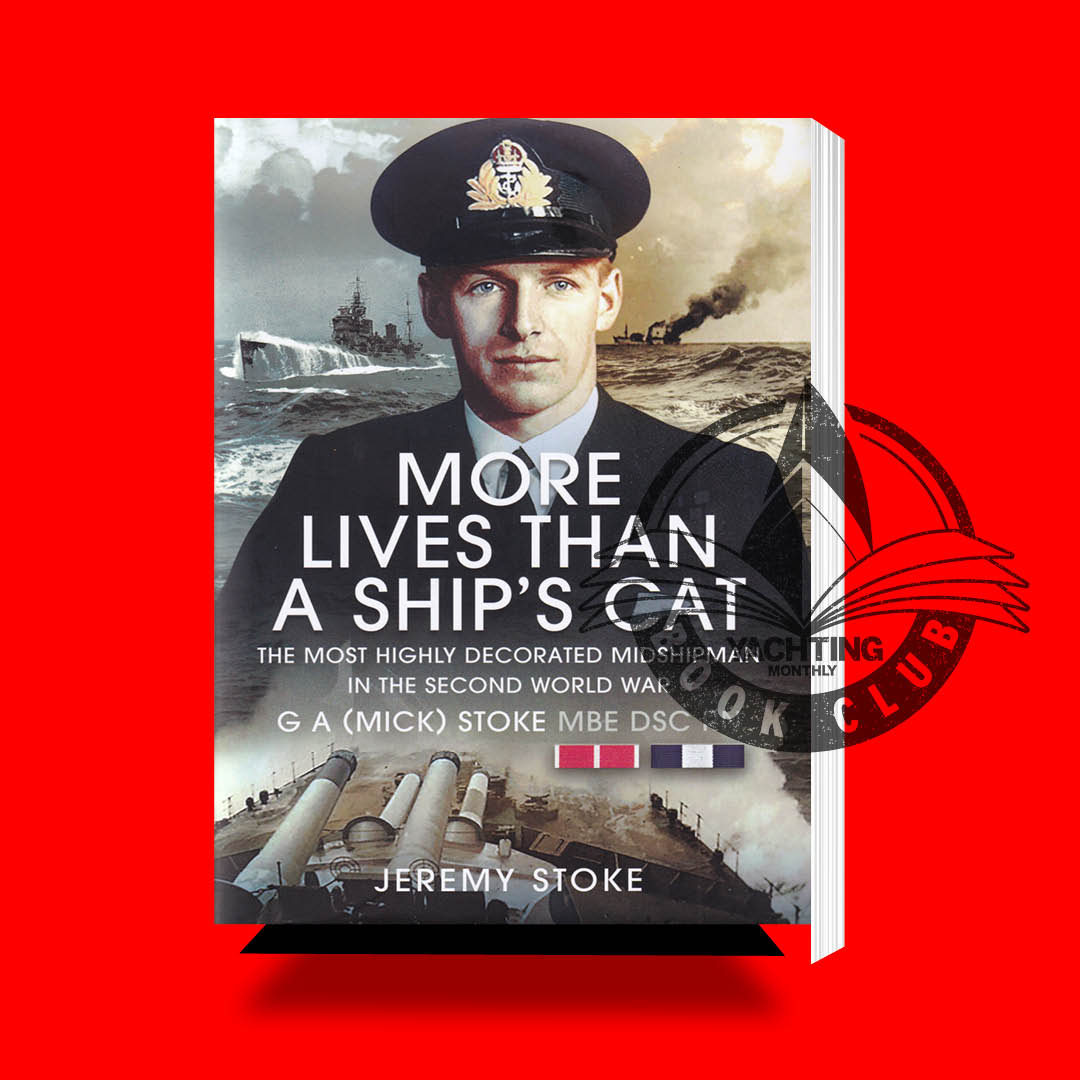

More Lives than a Ship's Cat: book review

This biography describes a Second World War naval career where medals matter and a young man can be seen to grow in confidence and self-belief.

G.A. ‘Mick’ Stoke was from a family with Jewish immigrant origins.

His father Samuel, who had fought in the First World War and anglicised his name, worked for Ellerman’s shipping lines and young Mick attended Westcliff High School in Essex.

He left, aged 18, in 1939 and took the surprising decision to apply for Special Entry to Dartmouth College to join the Paymaster Branch of the Royal Navy.

He was 19th of the 19 accepted, though 150 had applied.

When he arrived at HMS Britannia he discovered he was the only grammar school student among the ex-public school boys but reassured his parents that he wasn’t experiencing snobbery

‘The only difficulty is that my school has never played theirs.’

Perhaps it was because this was his first time away from home, Stoke was an assiduous letter writer and both his parents and (later) his fiancée preserved his letters scrupulously.

More Lives than a Ship’s Cat is written by his youngest son, Jeremy, who realised what a valuable inheritance had come his way.

It doesn’t require filial special pleading for Mick Stoke’s talents to be obvious.

One of the ways the Navy resembles a giant boarding school is in its regular production of reports, known as ‘flimsies’.

These represent the judgement of senior officers on the attitude and personality of the individuals under their command.

Mick Stoke won a lot of medals – the sub-title to the book describes him as ‘the most highly decorated midshipman in the Second World War’ – but the flimsies invariably focus on his qualities, describing his energy, enthusiasm, reliability, likeability as well as his personal bravery and skill in rugger and music.

Stoke served on warships, often cruisers such as HMS Glasgow and HMS Carlisle.

These were relatively large communities where a considerable amount of administration was needed and where a good secretary could be indispensable to a captain.

They were frequently in the thick of action, under fire from enemy warships and subject to prolonged aerial bombing.

For much of Stoke’s early career his postings were in the Mediterranean which soon became a crucible of direct warfare, especially during the protracted siege of Malta.

Shells and bombs don’t discriminate between ship-borne administrative and executive staff and there were several occasions when Stoke took a direct part in helping man a gun, participate in a rescue or move burning vessels.

Other opportunities for experience and personal development came when his various captains were sent ashore as staff officers.

When Captain Harold Hickling of HMS Glasgow – badly damaged by torpedo — was appointed Senior Office of the Inshore Squadron, off the coast of North Africa, he took his 19-year-old secretary into the Western Desert for four difficult months, February to June 1941.

The following year Stoke spent six months at Bone in Algeria working for the commanding officers of the Inshore Squadron.

He didn’t remain a midshipman.

Even within the regular Navy there are opportunities for accelerated promotion and Stoke was frequently recommended for these.

His letters as well as the flimsies make it clear that he almost always liked and respected the people he worked for, and they liked and respected him.

As he grew in personal confidence, and the exhaustion of war took its toll, he maintained his intense work ethic but could be impatient with those who didn’t measure up to his high standards.

Jeremy Stoke has done a fine job of using other written records such as Admiral Cunningham’s memoir, senior officers’ reports and personal recollections supplied to the BBC People’s War project to put his father’s letters in context. Read More...