Sony predicts phones to soon overtake DSLR cameras — is that really likely?

Sony is always on the cutting edge of mobile camera technology, and a recent report in Nikkei Japan indicates that the company believes its breakthroughs will see smartphones match and even overtake the capabilities of DSLR and mirrorless cameras as soon as 2024.

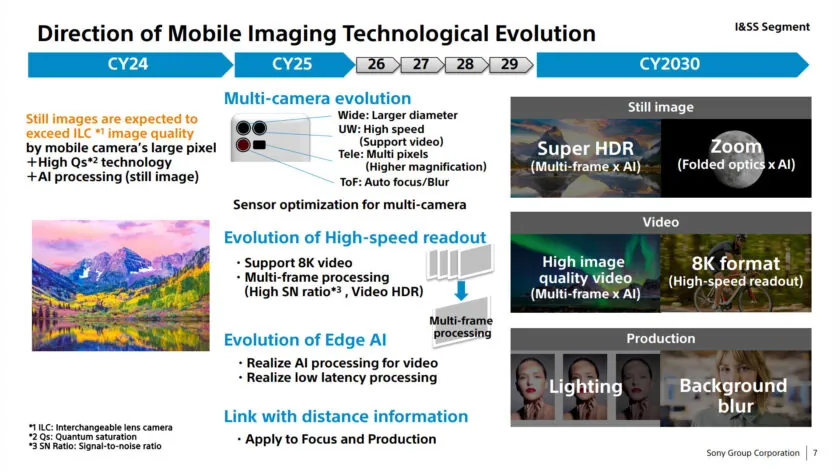

At a recent business briefing, President and CEO of Sony Semiconductor Solutions (SSS), Terushi Shimizu, noted that “still images [from smartphones] will exceed the image quality of single-lens reflex cameras within the next few years.” A slide from the same briefing points to 2024 as the timeline where Sony sees that smartphone “still images are expected to exceed ILC [interchangeable lens camera] image quality.”

Those are slightly different ways of saying the same thing: phones will surpass DSLR and mirrorless camera image quality in the next two to three years. Of course, there’s a wide variety of mirrorless cameras with capabilities and prices to suit a range of budgets. Beating the cheaper models isn’t as difficult as overtaking the premium tier. So is this just Sony marketing fluff or is there truth to this claim?

Mobile cameras continue to improve

There are several key components Sony cited to add confidence to its claim. First, mobile image sensors are expected to reach and potentially exceed one inch in size in the next two years. It’s worth noting that the Sony Xperia Pro I already boasts a 1-inch 20MP primary image sensor. However, due to distance constraints between the lens and sensor, Sony’s ultra-premium camera only uses 12MP of the sensor’s surface, the equivalent of a roughly 1/1.3 inch sensor that’s quite common in other flagship smartphones. This is a problem that Sony doesn’t directly address, and the limitations of the smartphone form factor will likely keep a lid on just how big mobile sensors can become.

Sony sees new sensors, AI, and high-speed readouts as the keys to overtaking DSLR cameras.

That said, Sony keenly highlighted the potential of its new two-layer CMOS sensor breakthrough. This new setup separates the manufacturing process for the photodiode and transistor layers, optimizing each more effectively. Previous designs have both elements on the same wafer. Sony states that the new structure saturates each pixel with twice as much light, greatly increasing the dynamic range and reducing noise in low light when compared to conventional back-illuminated image sensors.

Even if smartphone sensors can’t become big enough to rival APS-C cameras, smaller sensors will be able to capture much more light in the near future, closing the gap. It’s not yet known when this technology will make its way to smartphones, but it has appeared in Sony’s top-of-the-line mirrorless cameras.

Thirdly, Sony notes the growth in AI processing capabilities that, when paired with improved hardware, continue to push the boundaries of multi-frame HDR, longer-range zoom, and higher quality video recording. It’s undeniable that computational photography already helps smartphone cameras punch well above their station. Just see Google’s $599 Pixel 6, for example, as well as the broader trend of combining traditional image signal processing with machine learning silicon, both on-chip and in-device. Smartphone processing prowess already exceeds DSLR cameras and is likely to accelerate.

In addition to the presentation, Sony is also debuting the mobile industry’s first variable focal length camera in the Xperia 1 IV. Ranging from 85-125mm with a single lens, the periscope camera offers a DSLR zoom-lens-like experience in a mobile form factor. If it’s possible to expand the range of focal lengths, this technology could negate some of the issues stemming from the use of multiple image sensors, from costs and space, to image and lens quality inconsistencies. Perhaps one day, phones will do away with multiple cameras altogether.

Smartphone processing prowess already exceeds DSLR cameras and is likely to accelerate.

Combined with 8K high-speed readouts, improved depth information and software blur, and post-processing lighting adjustments, Sony is betting that it will be even harder to tell the difference between professional and smartphone pictures in just two short years.

Smartphones surpassing DSLR cameras, really?

There’s no doubt that smartphones still have some way to go before reaching the limits of the form factor, but how much farther they can go and how quickly is less clear cut. Yearly improvements have been slowing in many regards, with incremental improvements to image quality harder to come by each generation. But that’s more of a testament to how good smartphone photography has come in recent years. In good lighting and increasingly in low light, it’s often hard to fault high-end smartphone cameras.

However, as we mentioned, it’s difficult to fit larger image sensors into phones without significantly increasing the size of camera bumps and/or phone thickness. This is one of the reasons why periscope cameras exist, increasing the distance between the lens and sensor for a longer focal length without a bulky phone. The trade-off is the space required, plus the sensor has to be small to fit in the body at 90 degrees and therefore captures less light. Even when better sensors come along, how much room can phones sacrifice to the camera array rather than battery, haptics, speakers, and other components?

Although we might be approaching the 1-inch primary sensor, ultrawide and telephoto sensors are still tiny by comparison (typically still 1/2.5″ or below). It’s doubtful we’ll see a camera array with three large, high-quality sensors any time soon, but we have seen models dabble with two larger sensors. Phones may be stuck with varying levels of image quality from their primary, ultrawide, and zoom lenses, particularly in low light and HDR environments. Something that DSLR and mirrorless cameras don’t have to worry about (lens quality is the factor there).

Physics puts a limit on the size and quality of mobile image sensors and lenses.

The other half of the smartphone camera “quality” problem is lenses and aperture. Barring a few switchable aperture phones, handset cameras are stuck with fixed apertures and are therefore limited by ISO noise and shutter speed to balance their exposure. While this is fine in some instances, it’s an issue for advanced photographers who demand total control. Particularly for portraits and macro shots that demand a wide aperture for soft bokeh.

High-quality yet tiny lens elements that are free from distortion while still providing a wide aperture are very tricky and expensive to build. Even though smartphones boast seemingly wide apertures and focal lengths equivalent to popular full-frame camera lenses, they’re far from the real deal in terms of producing the distortion-free edges and creamy bokeh every photographer desires. Check out the examples below shot with the Samsung Galaxy S22 Ultra’s 22mm primary and 70mm telephoto versus a roughly equivalent mirrorless with 25mm and 80mm lenses. Read More...