The brain and blood vessels communicate through the immune system

By studying the formation of plaques in the arteries, a European research group that includes Italian scientists has revealed an unexpected connection between the circulatory, nervous and immune systems. In addition to suggesting that atherosclerosis may be partly controlled by the brain, Study 1 reveals a biological mechanism that may play a role in many other diseases.

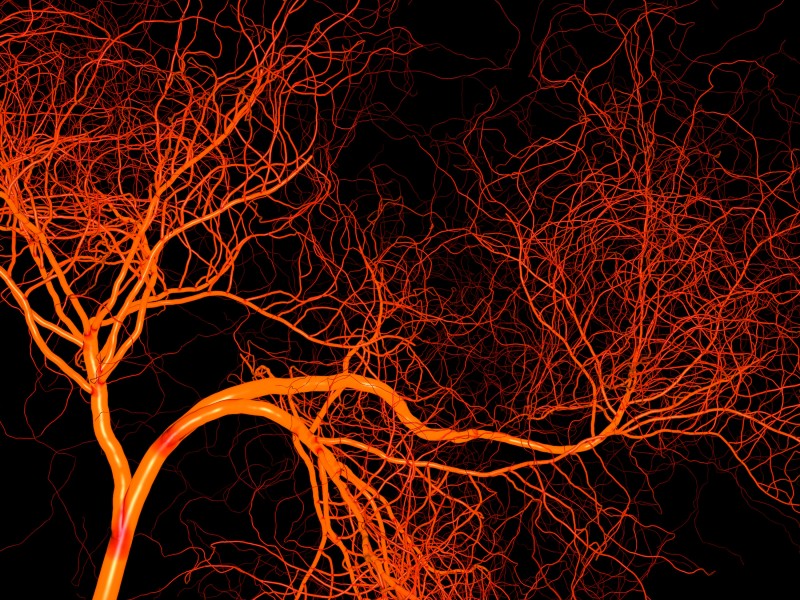

Atherosclerosis is the process by which fatty substances that circulate in the arteries can accumulate and form plaques. Over time, these plaques restrict blood flow and oxygen supply to vital organs, increasing the risk of heart attack and stroke. There are currently no therapies capable of reversing the process.

Arteries have two sides: the intima - the inner wall where the plaques are initially formed - and the adventitia - the outer wall, where the nerves flow. While most of the research so far has focused on the intima, the authors of the new study have looked at the role of adventitia.

A team led by Andreas Habenicht of the Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich had previously found that, as the disease progresses, immune cells infiltrate the arterial wall, forming aggregates that expand into the arterial tree. These cells give rise to arterial tertiary lymphoid organs (ATLO), which resemble normal lymph nodes, although their cells are likely derived from the spleen, and are involved in many diseases.

"By looking at the adventitia layer [in the vicinity of the ATLOs] we immediately found the endings of the peripheral nervous system," explains Habenicht. The logical consequence was to follow these peripheral nerves to the central nervous system. So the team injected a neurotropic virus directly into the adventitia of the mice. Within two days, the virus migrated and scientists were able to track it using an imaging technique called immunofluorescence. Eventually, they showed that there is an artery-brain circuit (ABC) made up of afferent neurons carrying sensory information from the adventitia to the brain and efferent neurons carrying instructions in the opposite direction.

To analyze the role of the circuit in the development of the plates, the German team joined forces with Daniela Carnevale and Giuseppe Lembo of Sapienza University of Rome and the Neuromed Institute of Pozzilli, who had previously demonstrated a connection between the vagus nerve - the longest in the body - and the immune functions in the spleen.

Using ultrasound to measure plaques in vivo, the Italian team was able to confirm that the density of nerve fibers near the plaques, as well as vagus nerve activity, increased in parallel with disease progression. They then disrupted the artery-brain circuit by chemical or surgical methods. "When we cut the innervation, the ATLOs disappeared, which was followed by an inhibition of the progression of the plate and its stabilization," explains Carnevale.

This multidirectional pathway involving arteries, immune cells and the nervous system represents a new paradigm that goes beyond vascular disease. "Since atherosclerosis is only one of many human diseases that have a local inflammatory component, the work suggests the possibility that other diseases may also have two-way functional communication with the nervous system," says David Dichek, professor of medicine at the university. of Washington, which did not participate in the study. Read More...