Cancer drug could potentially be used against malaria

A cancer drug currently in clinical trials has shown the potential to protect from, cure, and prevent transmission of malaria. The breakthrough finding by an international team that includes researchers at Penn State offers new hope against a disease that kills over half a million people annually, most severely affecting children under five, pregnant women, and patients with HIV.

The research team, led by researchers at the University of Cape Town (UCT), published their results in a new paper appearing Oct. 19 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"Disruptions to malaria vaccinations, treatment, and care during the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with increasing reports of resistance to first-line artemisinin-based combination therapies have led to an increase of malaria cases and deaths worldwide,” said Manuel Llinás, distinguished professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and of chemistry at Penn State. “The identification of new ways to treat the disease is crucial for malaria control. Ideal treatments would operate differently than current front-line drugs to circumvent current drug resistance and act on multiple targets or stages of the parasite’s life cycle in order to slow future resistance.”

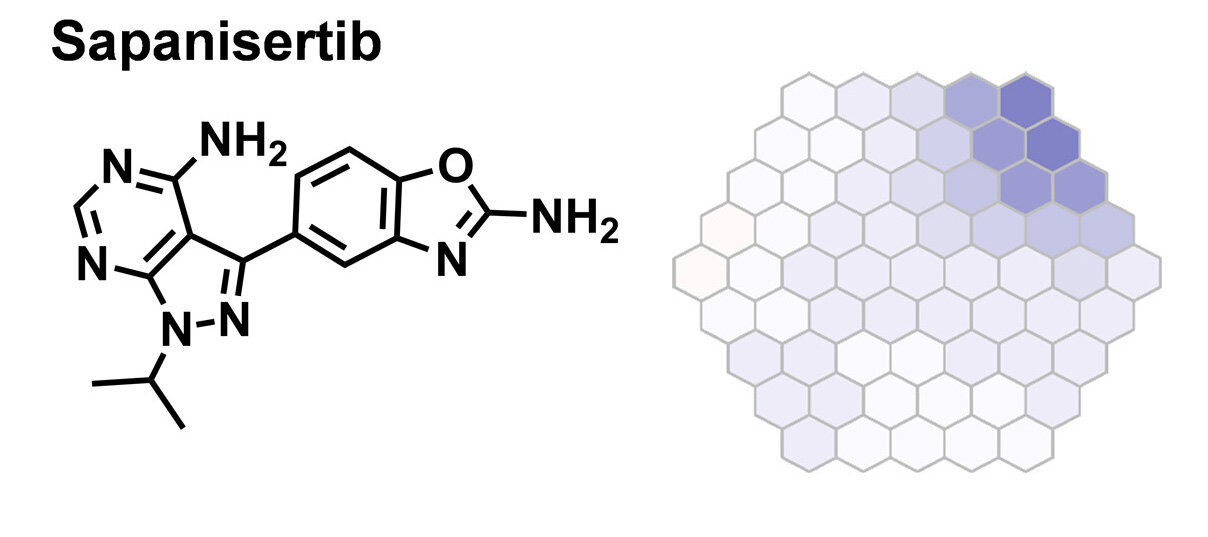

The research team explored whether sapanisertib, a drug that is currently in clinical trials for the treatment of various cancers, including breast cancer, endometrial cancer, glioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, and thyroid cancer, could be used to treat malaria.

They found that sapanisertib has the potential to protect from, cure, and block malaria transmission by killing the malaria parasite at several stages during its life cycle inside its human host. This includes when the parasite is in the liver, where it first grows and multiplies; when it is within the host’s red blood cells, where clinical symptoms are observed; and when it divides sexually within the host red blood cells to produce the transmissible forms of the parasite. The transmissible form is typically taken up by the female Anopheles mosquito during a blood meal and passed on during subsequent blood meals to infect another person, so killing the parasite should also prevent subsequent infections.

The researchers also established the mechanism by which sapanisertib kills the human malaria parasite and found that the drug inhibits multiple proteins called kinases in the malaria parasite.

Sapanisertib’s multistage activity and its antimalarial efficacy, coupled with potent inhibition of multiple protein targets — including at least two that have already been shown to be vulnerable targets for chemotherapeutic intervention — will underpin further research to evaluate the potential of repurposing sapanisertib to treat malaria. Read More…