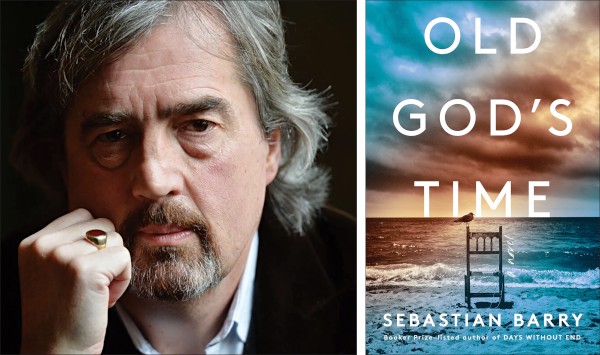

Sebastian Barry's New Novel Is a Family Affair

It’s a chilly afternoon in the tiny hamlet of Moyne, an hour and a half outside of Dublin, and Irish writer Sebastian Barry is in the converted 19th-century rectory where he’s been living for the past 20 years. “I’m sitting in the place where the rector used to write sermons to castigate his parishioners,” Barry says via Zoom. “And now I’m in here doing these books.”

One of Ireland’s most acclaimed literary figures, Barry is a poet, playwright, and novelist, twice shortlisted for the Booker Prize, who served as the laureate of Irish fiction from 2018 to 2021. His novels, all loosely interconnected, explore Irish history and the author’s ancestral past. They’ve sold more than 350,000 copies worldwide, according to Viking, his publisher, and have been translated into nearly 40 languages. His ninth novel, Old God’s Time, due out in March, concerns a widowed, retired police officer who’s reluctantly pulled into the murder investigation of a Catholic priest accused of abusing kids.

The book’s protagonist, a keeper of secrets, was inspired by a man Barry saw in 1964, when he was nine years old and living near the coast. “One day, while wandering around, I looked in through a door, which you’re not supposed to do as a child, and there was a man sitting alone in a wicker chair, looking out at the sea, smoking a cigarillo,” the author remembers. “He looked infinitely content. I never saw him again, but for the next 50 years I wondered what he was doing there. I thought maybe he was a retired person. And now that I’m supposed to be a retired person—though, of course, writers aren’t allowed to retire—it struck me, I wonder if he’d give me a book.”

Born in Dublin in 1955, Barry didn’t begin to read and write until he was eight years old. “Once I learned, there was no holding me back,” he says. “I was like a wild pony. I was gone, reading everything.”

His childhood was tumultuous and frothy with drama. “My mother, a theater actor, and my father, an architect, were self-absorbed and narcissistic,” he says. “It was a bohemian household, and I thought everyone’s mother went out in the evenings and came back late. I was surprised that other mothers stayed home. They obviously should be going to the theater. I thought the stage was another version of reality, which is a lovely mistake to make for a writer. And my father had a wild life—womanizing and the rest of it. There was an unmoored quality to the house, and it got progressively worse. I mean some parts were pacific, an ocean of good things, but there were these bloody islands of nastiness, and they have to be reckoned with.” Read More…