What are time crystals? And why are they so weird?

Physicists in Finland are the latest scientists to create “time crystals,” a newly discovered phase of matter that exists only at tiny atomic scales and extremely low temperatures but also seems to challenge a fundamental law of nature: the prohibition against perpetual motion.

The effect is only seen under quantum mechanical conditions (which is how atoms and their particles interact) and any attempt to extract work from such a system will destroy it. But the research reveals more of the counterintuitive nature of the quantum realm — the very smallest scale of the universe that ultimately influences everything else.

Time crystals have no practical use, and they don’t look anything like natural crystals. In fact, they don’t look like much at all. Instead, the name “time crystal” — one any marketing executive would be proud of — describes their regular changes in quantum states over a period of time, rather than their regular shapes in physical space, like ice, quartz or diamond.

Some scientists suggest time crystals might one day make memory for quantum computers. But the more immediate goal of such work is to learn more about quantum mechanics, said physicist Samuli Autti, a lecturer and research fellow at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom.

And just as the modern world relies on quantum mechanical effects inside transistors, there’s a possibility that these new quantum artifacts could one day prove useful.

“Maybe time crystals will eventually power some quantum features in your smartphone,” Autti said.

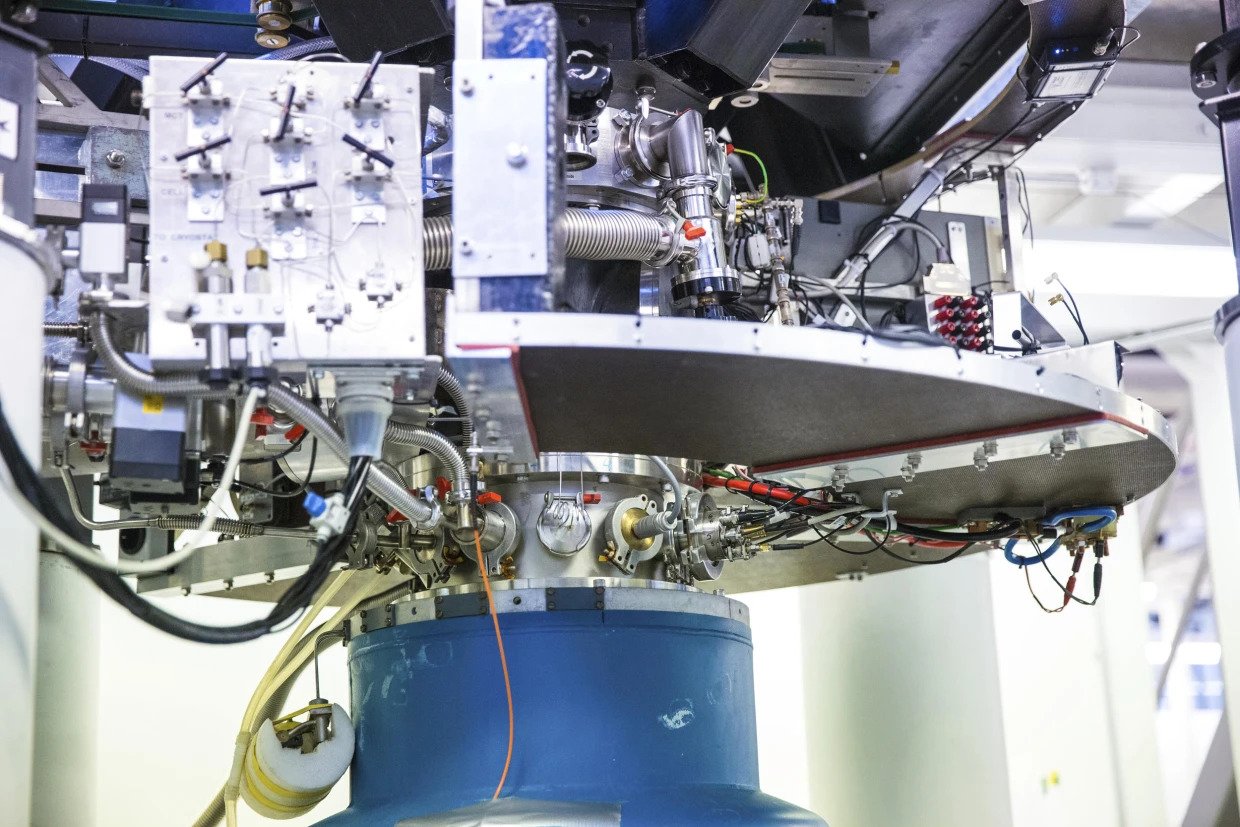

Autti is the lead author of a study published in Nature Communications last month that described the creation of two individual time crystals inside a sample of helium and their magnetic interactions as they changed shape.

He and his colleagues at the Low Temperature Laboratory of Helsinki’s Aalto University started with helium gas inside a glass tube, and then cooled it with lasers and other laboratory equipment to just one-ten-thousandth of a degree above absolute zero (around minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit).

The researchers then used a scientific equivalent of “looking sideways” at their helium sample with radio waves, so as not to disturb its fragile quantum states, and observed some of the helium nuclei oscillating between two low-energy levels — indicating they’d formed a “crystal” in time.

At such extremely low temperatures matter doesn’t have enough energy to behave normally, so it’s dominated by quantum mechanical effects. For example, helium — a liquid at below minus 452.2 Fahrenheit — has no viscosity or “thickness” in this state, so it flows upward out of containers as what’s called a “superfluid.”

The study of time crystals is part of research into quantum physics, which can quickly become perplexing. At the quantum level, a particle can be in more than one place at once, or it might form a “qubit” — the quantum analog of a single bit of digital information, but which can be two different values at the same time. Read More...