A massive rogue roaming our galaxy may be a black hole

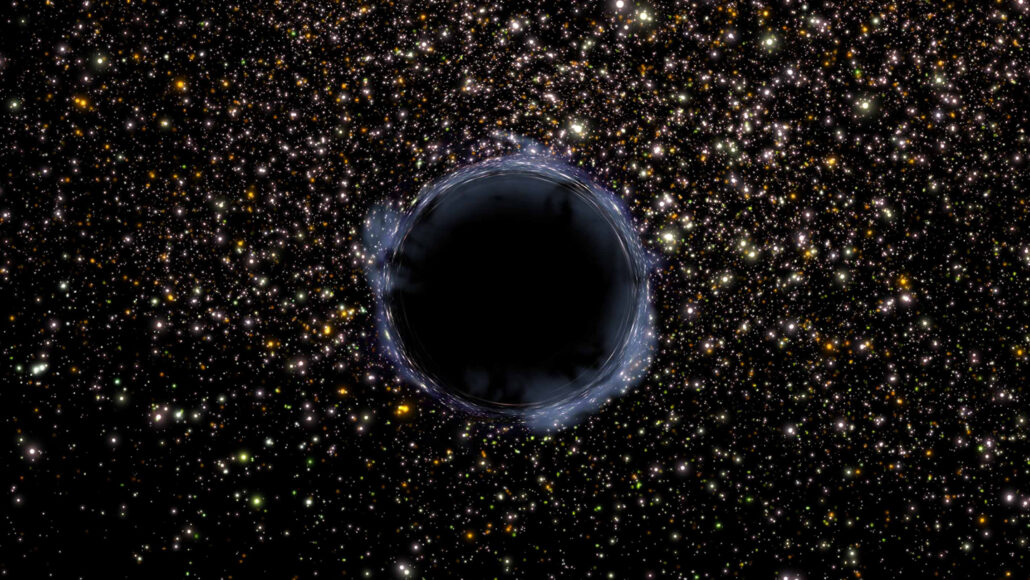

A solitary and massive celestial object is wandering our galaxy a few thousand light-years from Earth. It’s not too big, but its mass is greater than our sun’s. Astronomers suspect it might be the first loner black hole in the Milky Way found with a mass similar to our sun’s. Or it could prove to be one of the heaviest neutron stars known.

This wanderer first revealed itself in 2011. It wasn’t seen. Astronomers instead found it when its gravity briefly magnified the light from a more distant star. Back then, no one was sure what it might be. Now, two teams of astronomers have analyzed images from the Hubble Space Telescope. They’re still not entirely sure what the weighty object is, but they’ve narrowed down the list of candidates.

One group suspects this mysterious rogue is a black hole roughly seven times as massive as the sun. Make no mistake, its 94 authors say: “We report the first unambiguous detection and mass measurement of an isolated stellar-mass black hole.” They describe it in a paper due out soon in the Astrophysical Journal.

Not so fast, says another team of 45 scientists. They think it’s a bit lighter — a mere two to four times the weight of our nearest star. If true, that would make it an unusually lightweight black hole — or a curiously hefty neutron star. This group will share its findings in an upcoming issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Both neutron stars and stellar-mass black holes can form when massive stars — ones with at least several times the heft of our sun — collapse under their own gravity. This happens at the end of those stars’ lives. Astronomers now believe that about a billion neutron stars and roughly 100 million stellar-mass black holes lurk in our galaxy.

Neither of these types of objects is easy to spot. Neutron stars are tiny — only about the size of a city. They also produce little light. Black holes, regardless of their size, emit no light at all. To detect these objects, then, scientists typically observe how they affect what’s around them.

The massive mystery

To date, scientists have detected nearly two dozen stellar-mass black holes. (These are puny compared to their supermassive cousins that sit in the center of most galaxies, including our own.) Researchers found those relatively tiny black holes by observing changes in some of their neighbors. Sometimes, a black hole and a normal star will get caught in a spiral. Think of it as a dance.

But it’s a dangerous dance, as the black hole rips away matter from that companion star. As the star’s material falls onto the black hole, it emits X-rays. Telescopes orbiting Earth can detect that radiation. But scientists will find it hard to know how big a black hole was before it started dining on the star. And since birthweight is a key characteristic of a black hole, looking at black holes that are eating stars can confuse the picture. That’s why, Sahu says, “If we want to understand the properties of black holes, it’s best to find isolated ones” — like the new loner.

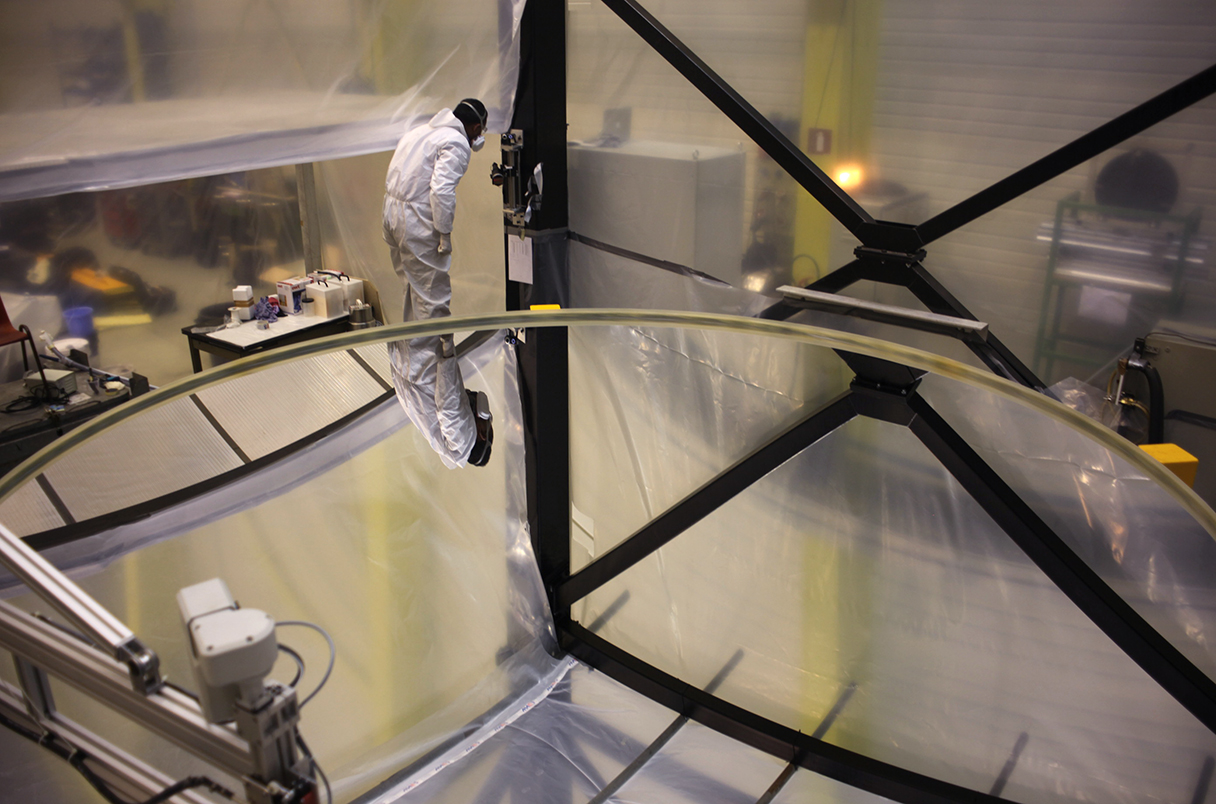

For more than a decade, researchers have been scanning the heavens for such isolated black holes. Hoping to spot these rogues, the scientists have looked for distorted starlight.

Einstein’s theory of general relativity states that the gravity associated with any massive object — even an unseen one — will bend the space in its vicinity. That bending magnifies and distorts the light of background stars. Astronomers refer to this as gravitational lensing. By measuring changes in the brightness and apparent position of stars, scientists can calculate the mass of a traveling object that’s acting like a lens. That technique has already turned up several exoplanets. Read More...