DNA data offers benefits many of us will never realise

High blood pressure increases your risk of stroke but having high blood pressure and diabetes increases that risk even more. Without a dictionary to interpret, you can know what DNA code is there, but you won't know what it means.

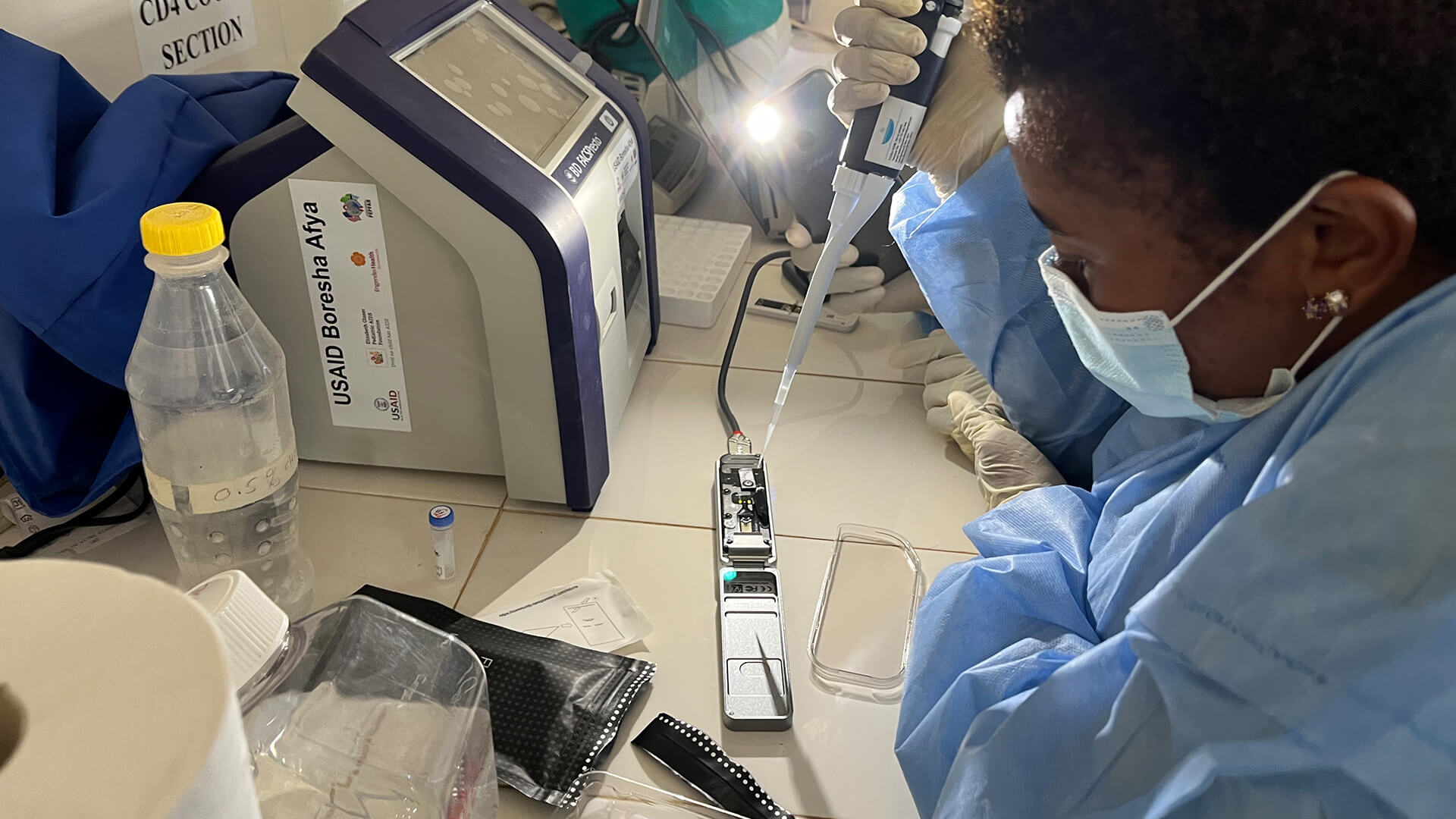

Collecting DNA data is not much help without the key to understanding what it all means. And that key is centralised health records.

It’s been 70 years since Watson and Crick revealed the double-helix structure of the DNA molecule. Now, instead of wondering at its structure, we chatter about DNA sequencing. We talk about how soon we will each have our own genomic data stored on our home computer. Or a time when a parent will be handed their newborn in one hand and their baby’s genomic code in the other. Or when our phones will beep to alert us that there is a new study showing that a portion of our sequence (or our child’s) has been linked to this or that disease. What we should be talking about is what will hold us back from realising these next steps.

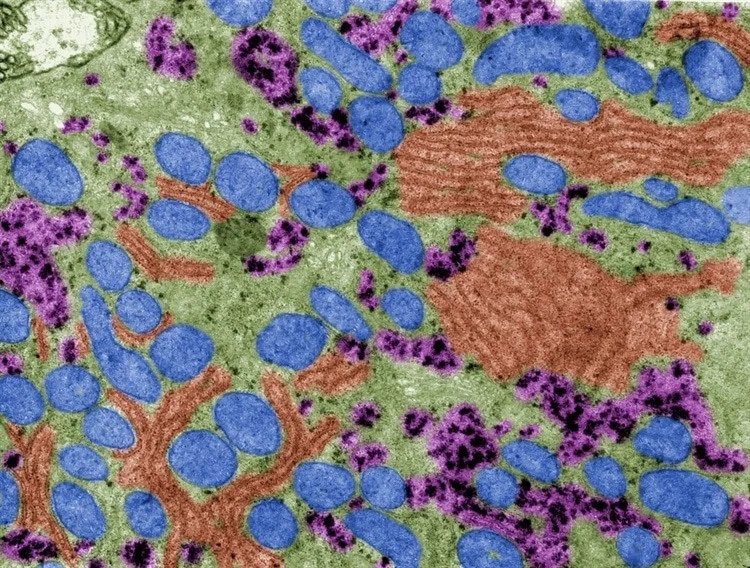

Our increasing technological ability, and reduced cost to sequence genomes, will play a part in making this happen in the next decade or two. But ability and cost are not the key to this future. Instead, comprehensive, centralised health records of populations will be the difference between realising this future, or not. Without health records we will not be able to know what the health implications of these sequences are. Science can read the DNA code, or ‘sequence’ DNA, faster and cheaper and create more raw data than ever before. But how do we interpret it? It's like having a book in a foreign language without a dictionary. The dictionary in this analogy is the complete health record. In the US each person’s dictionary has pages scattered across the country locked in different computer systems — some of which we know about, and others long forgotten (that trip to a community hospital one rainy Sunday night when your child wouldn’t stop coughing during that year you lived in Seattle, perhaps). Information will not make it into a computer in the first place if people can’t afford a visit to the doctor.

It is ironic that the US – a country that is among the world leaders in medical technology — will be among the least likely to move from sequence to meaning in this future. The fragmented and bloated state of an individual’s health information in the US stands in stark contrast to its ability to create technical and life-saving advances – some of the COVID-19 vaccines being among the most recent. In addition to producing the sequence quickly and affordably, we need to match the raw genomic data to the clinical data – all the mundane details about a person and their life – their height, weight over time, their illnesses big and small, their habits (smoking, drinking, exercise). Researchers must disentangle the effects that these attributes and habits have on each other and the genetic code. For example, we know that lack of exercise is not good, but it is worse in the context of being overweight. High blood pressure increases your risk of stroke but having high blood pressure and diabetes increases that risk even more. Read More…