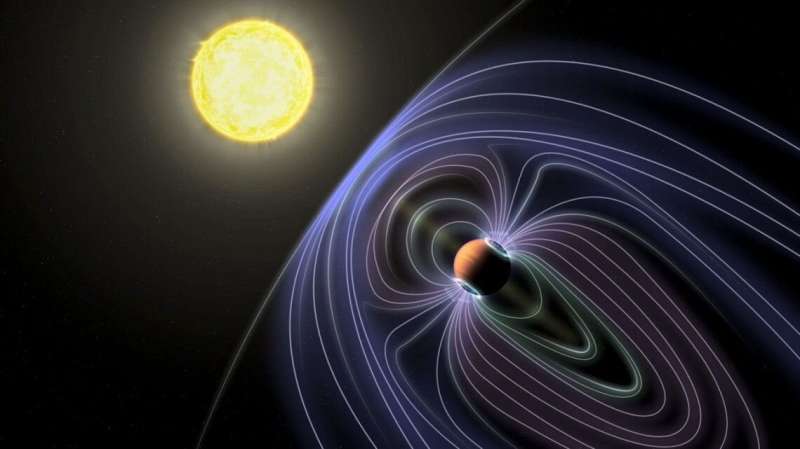

One exciting way to find planets: Detect the signals from their magnetospheres

Astronomers have discovered thousands of exoplanets in recent years. Most have them have been discovered by the transit method, where an optical telescope measures the brightness of a star over time. If the star dips very slightly in brightness, it could indicate that a planet has passed in front of it, blocking some of the light. The transit method is a powerful tool, but it has limitations. Not the least of which is that the planet must pass between us and its star for us to detect it. The transit method also relies on optical telescopes. But a new method could allow astronomers to detect exoplanets using radio telescopes.

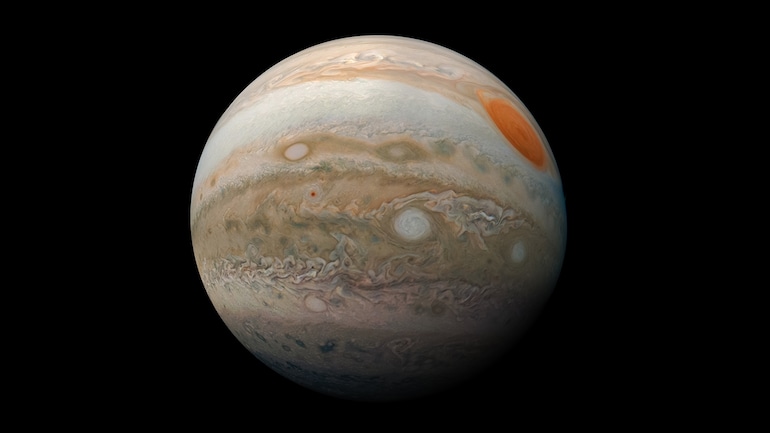

It isn't easy to observe exoplanets at radio wavelengths. Most planets don't emit much radio light, and most stars do. The radio light from stars can also be quite variable, due to things such as stellar flares. But large gas planets like Jupiter can be radio bright. Not from the planet itself, but from its strong magnetic field. Charged particles from stellar wind interact with the magnetic field and emit radio light. Jupiter is so bright in radio light you can detect it with a homemade radio telescope, and astronomers have detected radio signals from several brown dwarfs.

But there hasn't been a clear radio signal from a Jupiter-like planet orbiting another star. In this new study, the team looked at what such a signal might be like. They based their model on magnetohydrodynamics (MHD), which describes how magnetic fields and ionized gases interact, and applied it to a planetary system known as HD 189733, which is known to have a Jupiter-sized world. Read More...