‘Terribly courageous' – Atta Kwami's glorious posthumous mural unveiled at the Serpentine

Atta Kwami’s last work is still wet in places from its final retouchings by his widow, who painted it from his design. I sit next to her in the garden of Serpentine North by the many pots of colours she has been using to complete her late husband’s mural. “Our main worry was, ‘Is it an Atta Kwami?’” says Pamela Clarkson Kwami, herself a painter and printmaker. “If you went too far it became a kind of caricature.”

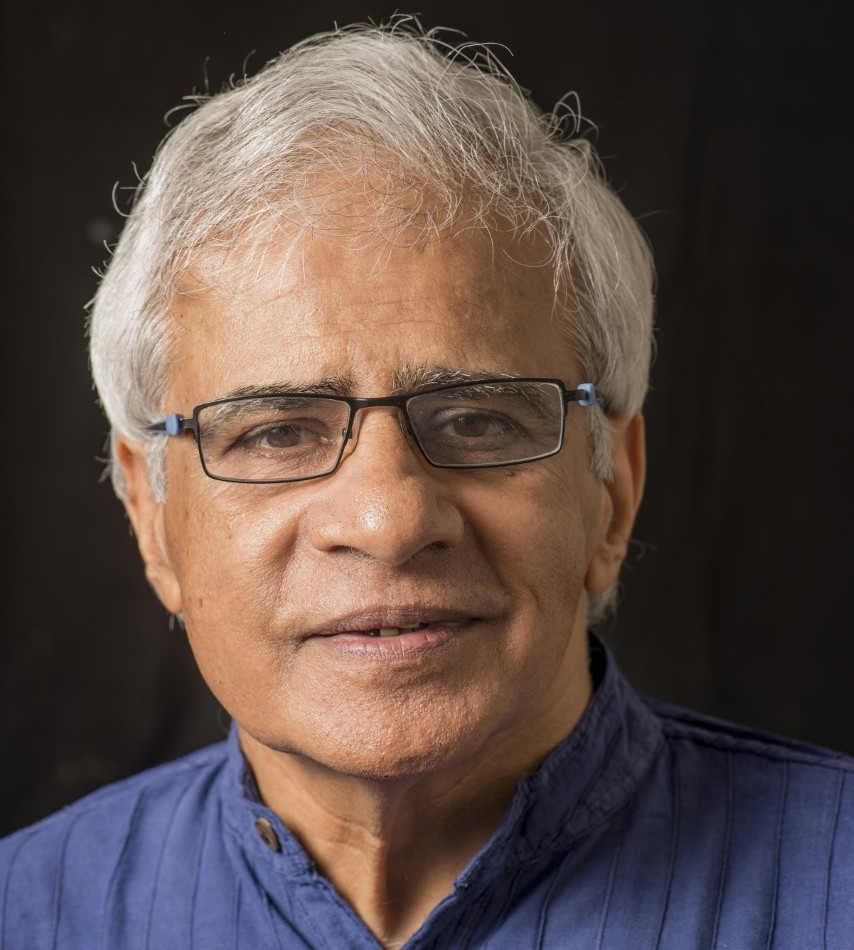

Kwami was a Ghanaian painter and art theorist with a generous, joyous abstract vision whose working life looked set to move into a new gear when he won the Maria Lassnig prize in 2021, an award for a “mid-career” artist that includes a public art commission for London’s Serpentine gallery. Kwami was born in 1956 and spent years teaching and researching before he could afford to paint full-time: a perfect recipient for this anti-ageist art prize. However, Kwami had cancer. He died last October just as his work was beginning to receive the acclaim it deserved – and with his design for a mural at the Serpentine yet to be realised.

Yet here it is and it is glorious. There’s something truly vital about Kwami’s big painting, a dance of rectangles in red, yellow, blue and many more interfolding planes of colour, against a grey bank of early September clouds. It was even better in the sunshine earlier, I am told. It will be great in all weathers, I’m certain, changing with the light and taking on new intensity as winter comes. For this is a painting that promises something: rebirth, redemption, freedom, justice … anyway, good things.

“I was thinking last night of the words that describe his work and you don’t want to say them because they sound naff,” says Clarkson Kwami. “One of them is joy and another is hope. You squirm slightly at the idea of it. But that is a terribly courageous thing to present to the world, isn’t it?”

Speaking to her I start to wish I’d met Atta Kwami. She fights back tears a couple of times yet presents him as objectively and unsentimentally as she can. “He could be a handful. He was very ambitious, and ambition is a difficult thing to deal with sometimes.” But they worked intimately side by side, them against the world: “I’ve been with him for 30 years and we’ve shared a studio and worked in the same space. He was a bit like an exile in his own country when he was in Ghana, partly because of his personality and partly because of the way he was working, which wasn’t necessarily in line with what anyone else was doing. It meant that we had each other and not many other people. We had each other as our main critics.” Read More...