Venus’ Outer Shell is Thinner and “Squishier” Than Previously Believed

While Earth and Venus are approximately the same size and both lose heat at about the same rate, the internal mechanisms that drive Earth’s geologic processes differ from its neighbor. It is these Venusian geologic processes that a team of researchers led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and the California Institute of Technology hope to learn more about as they discuss both the cooling mechanisms of Venus and the potential processes behind it.

The geologic processes that occur on Earth are primarily due to our planet having tectonic plates that are in constant motion from the heat escaping the core of the planet, which then rises through the mantle to the lithosphere, or the rigid outer rocky layer, that surrounds it. Once this heat is lost to space, the uppermost region of the mantle cools, while the ongoing mantle convection moves and shifts the currently known 15 to 20 tectonic plates that make up the lithosphere. These tectonic processes are a big reason why the Earth’s surface is constantly being reshaped. Venus, on the other hand, does not possess tectonic plates, so scientists have been puzzled as to how the planet both loses heat and reshapes its surface.

“For so long we’ve been locked into this idea that Venus’ lithosphere is stagnant and thick, but our view is now evolving,” said Dr. Suzanne Smrekar, who is a senior research scientist at NASA JPL, and lead author of the study.

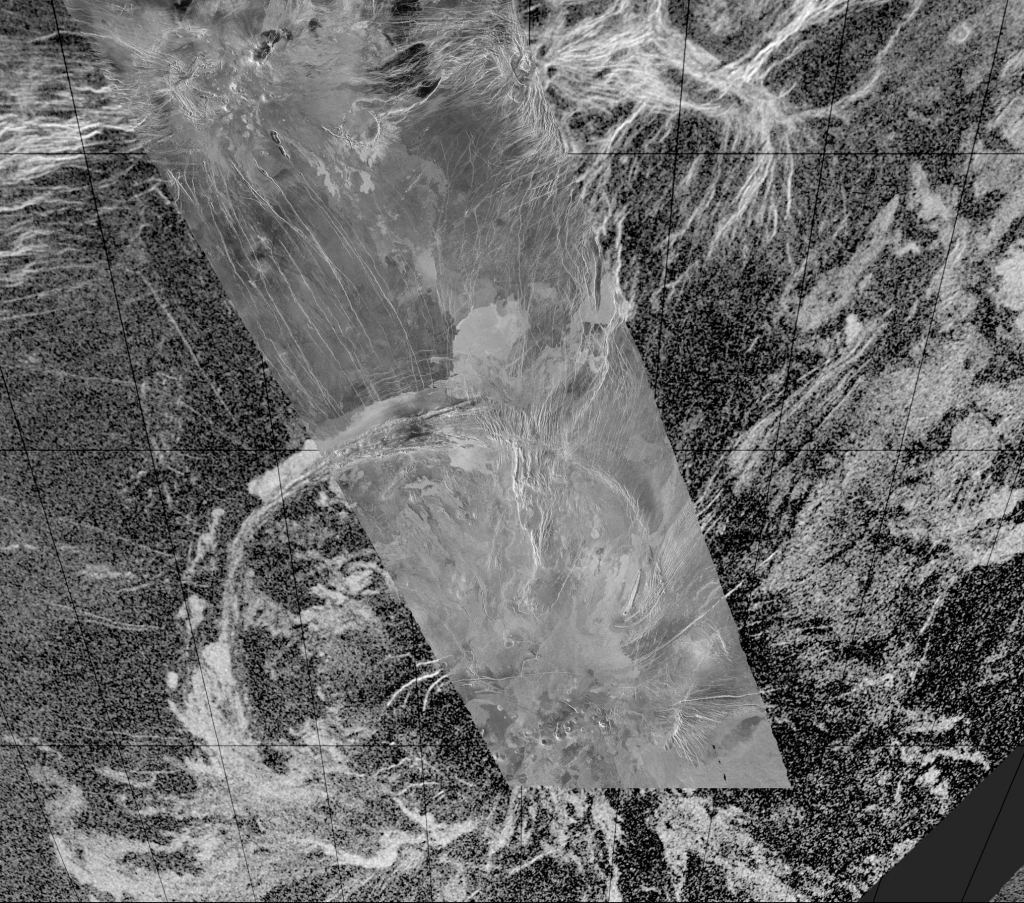

For the study, the researchers examined radar images from NASA’s Magellan mission taken in the early 1990s depicting quasi-circular geological features on Venus’ surface known as coronae. The reason why the images were taken using radar is because Venus’ atmosphere is so thick that normal images taken in the visual spectrum are unable to penetrate Venus’ thick, cloudy atmosphere.